All oak trees are susceptible to oak wilt.

Texans can do their part to protect oak trees from oak wilt this spring.

Oak wilt is one of the deadliest tree diseases in the U.S., killing millions of oaks in 76 counties of Central, North and West Texas, but its impact can be mitigated.

Prevention is key to stopping the spread of oak wilt, said Demian Gomez, Texas A&M Forest Service regional forest health coordinator. Any new wound, including from pruning, construction activities, livestock, land or cedar clearing, lawnmowers, string trimmers and storms, can be an entry point for the pathogen that infects trees.

“With wounds being the best entry point for the disease, landowners should avoid pruning or wounding trees from February through June,” Gomez said. “And no matter the time of year, to decrease the attractiveness of fresh wounds to insects, always paint oak tree wounds.”

How it spreads

Oak wilt can spread two ways – above ground or underground. (Texas A&M Forest Service photo)

Oak wilt is caused by the fungus Bretziella fagacearum. The fungus invades the xylem – the water-conducting vessels of the trees – and the tree responds by plugging the tissues, resulting in a lack of water to the leaves, slowly killing the infected tree.

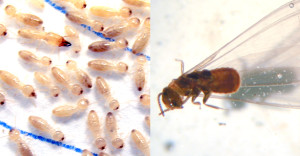

Oak wilt can spread two ways – above ground or underground. The disease is spread above ground more rapidly this time of year, in late winter and spring, because of high fungal mat production and high insect populations.

During this time, oak trees that died may produce spore mats under the bark. The fruity smell from these mats attract small, sap-feeding beetles that can later fly to a fresh wound of another oak tree and infect it, starting a new oak wilt center.

The second way oak wilt can spread is underground by traveling through interconnected root systems from tree to tree. Oak wilt spreads an average of 75 feet per year by the root system.

All oaks are susceptible to oak wilt. Red oaks are the most susceptible and can die in as little as one month after being infected.

Live oaks show intermediate susceptibility but can spread the disease easily due to their interconnected root systems. The interconnected root systems in live oaks are responsible for most tree deaths and spread of oak wilt in Central Texas. White oaks are the least susceptible, but they are not immune to infection.

Oak wilt is often recognized in live oaks by yellow and brown veins showing in leaves of infected trees, known as venial necrosis. Currently, it may be difficult to diagnose due to seasonal transitioning of oak leaves in the spring – when evergreen oak trees shed their old leaves while simultaneously growing new leaves.

The signs can be seen on a majority of leaves when a tree is fully infected. Landowners should contact a certified arborist if they are unsure if their tree is infected.

“For red oaks particularly, one of the first symptoms of oak wilt is leaves turning red or brown during the summer,” said Gomez. “While red oaks play a key role in the establishment of new disease centers, live oaks and white oaks move oak wilt through root grafts.”

How to fight

To stop the spread of oak wilt through the root system, trenches can be placed around a group of trees, at least 100 feet away from the dripline of infected trees and at least 4 feet deep, or deeper, to sever all root connections.

Another common management method is fungicide injection. The injections are only a preventative measure to protect individual trees. The best candidates for this treatment are healthy, non-symptomatic oaks up to 100 feet away from symptomatic trees.

Other ways to help prevent oak wilt are to plant other tree species to create tree diversity in the area; avoid moving oak firewood before it is seasoned; and talk with your neighbors about creating a community prevention plan. Infected red oaks that died should be cut down and burned, buried or chipped soon after discovery to prevent fungal mats that may form the following spring.

Not only is saving oak trees important for our ecosystem and health, but oak wilt can also reduce property values by 15-20%.

Some cities and municipalities, including Austin, Lakeway, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio and Round Rock, have programs in place with municipal foresters dedicated to managing the disease. Texans can also contact their local Texas A&M Forest Service representative with any questions about this devastating disease.

For more information on oak wilt identification and management, visit https://texasoakwilt.org/ or Texas A&M Forest Service’s website at https://tfsweb.tamu.edu/.