In 2012 Dallas was the national epicenter of a West Nile epidemic. A mild winter and very hot summer combined to make conditions that resulted in approximately 400 reported cases and 19 deaths in Dallas county alone. While 2015 has not approached the mosquito numbers or disease transmission potential of 2012, this year’s data suggests that risk for getting a WNV infection from a mosquito is peaking higher than any time since then.

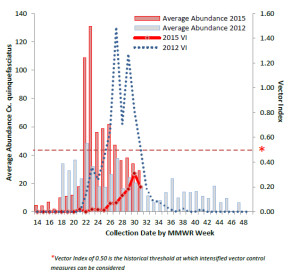

Average mosquito trap catches (bars) and the Vector Index (VI) of disease risk (lines) for West Nile Virus in Dallas County in 2012 and 2015. The VI for Aug 2015 is the highest seen since

Traditionally the potential for WNV transmission peaks in August and this year looks like no exception. Data published this week by the Dallas County Health and Human Services shows a key measure of disease risk (the Vector Index) to be higher this month than at any time since 2012. The vector index peaked on Aug 1 at 0.31. In comparison in 2013 and 2014 the VI reached only 0.19 and 0.14, respectively. A VI of 0.5 is considered high enough to justify intensified vector control methods like aerial spraying.

Though numbers of WNV are still considered low for our area (only 3 reported cases this summer), there have already been 3 cases of Chikungunya (out of 9 cases reported in the state), a disease that wasn’t even on our health officials’ radar in 2012. So far these appear to have been cases picked up from out of country travel, but anyone infected with this disease can spread it back to mosquitoes locally. This has resulted in a number of locally acquired cases in Florida and could easily happen here.

All this to say that all of us should be taking special care to protect ourselves from mosquito bites this time of year. Don’t assume that because it’s not been raining, you don’t have to look for sources of standing water. As irrigation and septic systems continue to flow, and creeks begin to dry up, there are plenty of mosquito breeding sites around. And don’t assume that because you can go out during the day and not see mosquitoes, you don’t need repellent when out at night. The Culex mosquitoes that are our primary disease carrying mosquito come out primarily after dark.

On the other hand, anyone travelling to the Caribbean or Central America should also be diligent to wear repellent day and night to protect against Chikungunya, which is carried by day-active Aedes mosquitoes.

As the lazy days of summer pass slowly, consider this reminder. Don’t get lazy about protecting you and your family from mosquito-borne disease risk.