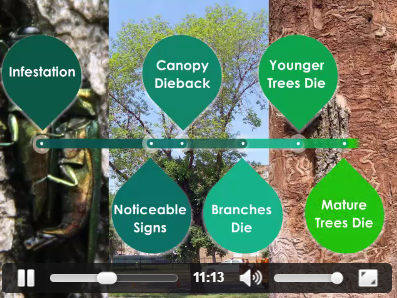

Walnut caterpillars may strip leaves from portions or all of the canopy of pecan or walnut trees. However severe damage is unusual and late-season damage rarely harmful to the tree.

Finding a caterpillar on a plant or tree in your backyard can be cause for excitement. But they should be little cause for concern, especially during the fall months.

To most human eyes caterpillars are alien creatures. With their squishy, worm-like bodies, and accordion gait, they are weirdly unique among other insects. Some are large and fantastically showy. Others have ominous-looking barbs and hairs. And some are skillfully camouflaged, nearly invisible among the leaves and shadows. When gardeners do encounter a caterpillar, reactions range from “cool!” to “yuck!!!”

Caterpillars, of course, are the larval stage of moths and butterflies. What many good gardeners fail to appreciate, however, is the essential role they play in the backyard food chain. Birds rely most heavily on caterpillars for food. Without caterpillars to feed on, we wouldn’t see many of our favorite backyard birds.

But what about the damage they cause? Most gardeners have been disappointed at finding a favorite flower or tomato plant eaten to the stems by hungry caterpillars. While it’s true that caterpillars can be devastating to crops and the occasional garden flower, most caterpillars, especially those found on trees and shrubs in the fall, pose little danger to the long-term health or beauty of our yards.

The yellow bear caterpillar, sometimes called a woolly bear, is a generalist feeder on weeds and low plants. This one is feeding on water lily.

Spring and summer are times of growth and productivity for plants. Photosynthesis is at its peak during summer when the sunlight is strongest and days are long. At this time, deciduous plants can withstand 20-40% defoliation with no ill effects; though more severe defoliation can cause stress and loss of vitality.

During fall, growth slows. Fruits like pecans and acorns fill out, and new growth halts as trees and shrubs prepare for winter. In a few weeks, leaves will turn and drop, further evidence that plants have little use left for their greenery.

For this reason, caterpillars that feed on deciduous plants during this time of year rarely cause significant harm to our plants. Nevertheless, Extension offices get many calls from worried gardeners about caterpillars in the fall. Walnut caterpillars are common now on pecans, walnuts and hickory trees. Various caterpillars are active on our many oak tree species. Hornworm caterpillars and woolly bear caterpillars are also frequently seen feeding on a variety of ground-hugging, herbaceous plants. As a rule of thumb, however, none of these should require special attention or an insecticide treatment.

Pandorus sphinx moth caterpillar with parasite cocoons attached. This caterpillar will not successfully complete its development due to its weakened state after feeding by the dozens of parasitic larvae that have now emerged and are resting for their eventual emergence as tiny adult wasps.

Fall is also a good time to observe beneficial predators and parasites of late season caterpillars. Paper wasps and solitary wasps are active now storing up juicy caterpillars to feed their offspring. Also tiny parasitic wasps are attacking and emerging from many kinds of caterpillars. Look for oval-shaped, white cocoons hanging from the backs of caterpillars. These cocoons are evidence of an earlier attack by a tiny wasp that laid eggs in or on the caterpillar. Caterpillars wearing these silken cases are doomed, having been previously weakened by the wasp larvae feeding on their insides.

Gruesome as it sounds, these parasites and the many predators keep caterpillars from being more serious pests. Most years caterpillars are rarely seen in a typical backyard, although there may be the occasional year where certain caterpillars are especially abundant, and may cause defoliation. But our trees and native plants have survived insect attack successfully for many years, long before humans were around to care and worry about them. Unless a tree is under stress from other problems, rarely do caterpillars cause much damage.

Flannel moth caterpillars, sometimes called “asps”, hide rows of venomous bristles under their long hairs. Avoid touching these small caterpillars to avoid a painful sting (right).

Standing out from the common caterpillar crowd, are some of the stinging caterpillars. While most fall caterpillars are harmless, a few types of stinging caterpillars deserve our respect. Over the past month I’ve had a few inquiries about flannel moth caterpillars, known to most Texans as “asps”. These hairy, odd-looking caterpillars feed on oaks and elms, and yaupon shrubs. When finished eating they crawl out of trees to pupate on fences and the sides of buildings. Asps bear a set of barbed spines under their fur coat, that can cause a painful skin reaction. Give these guys a wide berth, or be careful to wear heavy gloves if you must handle these critters.

Instead of worrying about caterpillars in the yard, embrace them! They are providing food for wildlife, and in moderation are a sign of a healthy environment. And on top of that, they are fun to watch and identify. For additional reading and identification, check out these guides for the gardener:

- Caterpillars of Eastern North America by David L. Wagner. Princeton Field Guides, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 512 pp. Still the most comprehensive field guide to caterpillars yet published in the U.S. Beautiful photos of both adults and caterpillars of macrolepidopteran moths and butterflies. A must-have reference with lots of useful information for the serious naturalist and entomologist alike.

- Owlet Caterpillars of Eastern North America by David L. Wagner, Dale F. Schweitzer, J. Bolling Sullivan and Richard C. Reardon. 2011. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. 576 pp. I thought that Caterpillars of Eastern North America was pretty thorough until this book came out and realized how many species there were to know from just one moth family group. The Noctuid moths constitute the most diverse Lepidoptera family, and in this guide they are covered along with three other related families now called owlet moths. Another beautiful guide from David Wagner and colleagues, with stunning photography. Alas, not a Texas guide, but still quite useful in helping identify moth caterpillars in the eastern half of the U.S.

- Caterpillars in the Field and Garden: A Field Guide to the Butterfly Caterpillars of North America by Thomas J. Allen, James P. Brock and Jeffrey Glassberg. 2005. Oxford University Press, USA. 240 pp. When it rains it pours. After many years with few references to caterpillars, this book and the Wagner book both appeared in 2005. This volume focuses almost exclusively on butterfly larvae, which make up far less than half of all caterpillars; but it is well done and will be useful for butterfly gardeners and those wishing to supplement their knowledge of the lesser known life stages of butterflies.