Spread in the United States

The Turkestan cockroach was first noticed in the US in 1978, around the former Sharpe Army Depot in California, followed shortly after by appearances at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, and several other military bases. Researchers believe the species arrived on military equipment returning from central Asia, perhaps Afghanistan. Since then, the species has been rapidly replacing the common Oriental cockroach (Blatta orientalis) in urban areas of the southwestern United States, thus, gaining the attention of pest management professionals and research/extension entomologists. Though the spread of Turkestan cockroaches in the US is believed to have been initially facilitated by military equipment returning from the Middle East, their proliferation (and further human-mediated spread) has been significantly increased by their sale on the internet for the pet trade. The same attributes that make this species a popular feeder insect, contribute to why it has success outside of captivity, and its ability to displace species. Turkestan cockroaches are known to infest a variety of habitats such as semi-arid deserts, water meter boxes, compost piles, leaf litter, potted plants, sewer systems, and cracks in concrete walkways (See Texas Invasives webpage below).

Origin and Characteristics

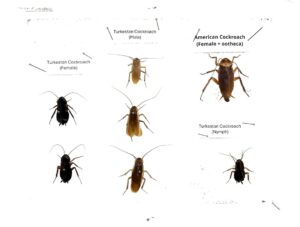

The Turkestan cockroach, scientifically known as Blatta lateralis, also known as the rusty red cockroach or red runner cockroach, is native to an area extending from northern Africa to Central Asia. Adult males, often confused for American cockroaches (Periplaneta americana), are brownish orange/red, slender, and have long, yellowish wings which allow them to attract females and to glide. Compared to adult American cockroaches, adult male Turkestan cockroaches are smaller in size and, in my opinion, lighter in color. On the other hand, adult female Turkestan cockroaches are often confused for the Oriental cockroach (Blatta orientalis), due to their dark brown to black coloration, with light cream-colored markings on the pronotum and a more obvious cream-colored stripe along the edge of its wings. They are broader than Turkestan males and have short vestigial wings. Nymphs are also dark in color, similar to the female, but lack wings.

As previously mentioned, Turkestan roaches have gained popularity in the pet trade, particularly among reptile/arthropod breeders. This is due to a couple of factors:

1) their inability to climb smooth surfaces (like a breeding tank), preventing escape (remember: males are capable of jumping/gliding, and therefore, can indeed escape).

2) their rapid breeding cycle and larger reproductive capabilities, which ensure a continuous supply of food

3) they are hardy cockroaches and easily maintained compared to other common feeder insects (crickets, mealworms, waxworms, and other roach species)

The Turkestan cockroach is primarily an outdoor insect and is not known as an aggressive indoor pest. However, it can become a significant indoor pest in specific localities or environments. When encountered indoors (and, in my experience, in the landscape), males are more commonly seen than females, due to their ability to “fly” and an attraction to lights. Turkestan cockroaches are better adapted to hot, dry climates, which gives them an advantage in many regions of the United States. As such, they have become the most prevalent cockroach species in many urban areas, particularly in the Southwest.

Presence in Texas

Turkestan cockroach populations are on the rise in Texas, and they seem to be spreading. Turkestan cockroaches, like many invasive arthropods, are spread quickly by hitching a ride in various supplies and goods that are moved around (potted plants, bags of soil, firewood and lumber products, and even moving boxes and trucks with unsuspecting movers). We call this “human-mediated jump dispersal” and depending on the hardiness/adaptability of the invader, there are rarely any negative effects on the population of re-located individuals when invading a previously un-infested area.

According to most reports I have come across online, Turkestan cockroaches have been reported in El Paso, Texas. That being said, when I moved to Dallas in 2022, PMPs mentioned they had seen this species in our area – specifically, McKinney, Texas. That was the last I had heard of their presence in North Texas.

Imagine my surprise when I was walking outside of a newly built apartment complex in Allen, Texas (just south of McKinney) and see the strangest “gliding” behavior of what I initially thought was an American cockroach. Upon further inspection, I start to see tens of these gliding individuals. I am going to try to explain this… think about how grasshoppers will jump and flutter in front of you as you walk a path through a field/yard and then combine that with the ability to run like a cockroach. It was so unusual! I bent down into the landscaped area and that’s when I saw a dark brown/black roach being pursued by 3 or more males (remember, they are sexually dimorphic). Then came my “ah-ha!” moment and I realized I was witnessing a full-on Turkestan cockroach infestation in North Texas, y’all!

Conclusion

The Turkestan cockroach, Blatta lateralis, exerts a substantial impact on the ecological balance, primarily through water contamination and the propagation of diseases. This species exhibits a predilection for habitats such as domestic water meters and sewer systems. The cockroach’s residence in sewer systems poses a significant health risk, given its potential to act as a vector for various diseases. The rapid reproduction rate of this species intensifies these issues. Consequently, the presence of the Turkestan cockroach in Texas is a matter of significant concern. Upon infestation, management strategies typically involve the use of desiccation dust and baits. Its spread in Texas and other parts of the United States underscores the need for effective pest control measures and increased public awareness about this invasive species.

Reference Materials and Additional Resources:

Texas Invasive Species Institute

The Invasive Turkestan Cockroach is Displacing the Oriental Cockroach in the Southwestern U.S.

Turkestan Cockroaches Have Made Themselves at Home in California

Tina Kim, Michael K. Rust, Life History and Biology of the Invasive Turkestan Cockroach (Dictyoptera: Blattidae), Journal of Economic Entomology, Volume 106, Issue 6, 1 December 2013, Pages 2428–2432, https://doi.org/10.1603/EC13052