The good news is that the number of Lyme disease cases appears to be low and even declining in Texas. The bad news is that the tick that carries Lyme disease is well established in Texas and its range appears to be expanding.

Even though we don’t hear as much about it here in Texas, Lyme disease is the most common insect-transmitted disease in the U.S.–even more than west Nile virus. Caused by a bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi, and carried by infected black-legged ticks, Lyme can be a chronic debilitating disease of humans. Initial symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue and skin rash. Left undiagnosed and untreated, the disease can spread to the heart, joints and the nervous system.

By far the greatest number of Lyme disease cases, over 20,000 a year, are seen in the upper midwest and northeastern states. But Texas sees dozens of cases every year, mostly within the Golden Triangle region between Houston, Dallas and Austin. Some of these cases occur in individuals who have been bitten by ticks outside the state, but many infections occur when people come in contact with a tick here in Texas.

The black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularis, is thought to be the principal vector of Lyme disease in Texas. The adult is active during the fall and winter, and nymphs are active in spring and summer. Both nymphs and adults are capable of transmitting the bacterium to humans.

Doctors are concerned about rising number of cases in some parts of the country, and a geographical expansion of the area where Lyme disease occurs. A new study by CDC researchers showing an expansion in the range of the tick might explain the spread of the disease.

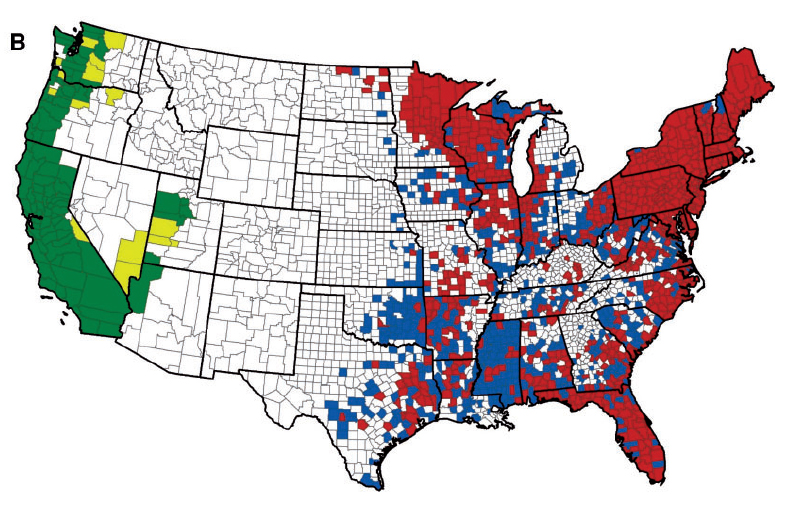

2015 distribution of two species of blacklegged ticks in the U.S. Red and blue counties show the current range of the eastern blacklegged tick and green counties show the range of the western species of tick. (Eisen et al. 2016). Red and dark green shaded counties are where 6 or more ticks have been recorded in a year, and the tick is considered established.

Researchers have now found blacklegged ticks in 49% of all U.S. counties spread across 43 states. This represents an increase of almost 45% from 1998, when tick distribution was last mapped. The status of nine Texas counties changed from “previously unreported” or simply “reported”, to a higher status of “reported” or “established” (six or more ticks or two or more life stages collected in a year). The tick has now been reported from 71 (28%) out of the 254 Texas counties.

So what to make of all this? We know that Texas has the Lyme disease carrying tick, and that a few to dozens of people contract the disease from outdoor activity in Texas every year. And these numbers are likely underestimates, because Lyme disease is less frequently tested for here than in parts of the country where it is known better and more common. We also know that the ticks that carry Lyme disease are doing well enough to be showing up in more, rather than fewer, counties every year.

This research reminds me that any time I venture outdoors I need to be aware of ticks and the possibility of bringing home a tick or an infection (Lyme disease is only one of several tick-borne diseases found in the state). We should all use tick repellent and inspect ourselves and our companions for ticks when venturing outdoors.

Permethrin-containing sprays applied to clothing are the most effective repellents for ticks, though skin applied repellents can also help. Learn how to remove a tick by grasping close to the head with tweezers or protected fingers to pull straight out. The sooner a tick is removed the less chance for disease transmission. The CDC advises to avoid folklore remedies such as “painting” the tick with nail polish or petroleum jelly, or using heat to make the tick detach from the skin. Your goal is to remove the tick as quickly as possible–not waiting for it to detach. Also, heat and suffocants, like grease, may actually stimulate the tick to salivate, increasing your potential for infection.

Although chances of infection with a tick-borne disease in Texas are relatively low, should you experience a rash, fever, headache, joint or muscle pains, or swollen lymph nodes within 30 days after being bitten by a tick, tell your doctor . Knowing that a tick might have been involved will provide her with information she needs to properly diagnose the problem.