Kudzu bugs are beetle-like in appearance, but like all true bugs have sucking mouthparts. Photo by Dan Suiter.

Last week Texas became the fourteenth state with verified populations of kudzu bug. An alert county Extension agent, Kim Benton, reported kudzu bugs from a home garden in Rusk, TX, south of Tyler. The bugs were clustered on eggplant and other vegetables before being transplanted into the garden.

The kudzu bug saga in the U.S. began in October 2009 when millions of small, pill-like bugs startled homeowners across nine counties in northeast Georgia. The never-before-seen insects covered the sides of homes by the thousands, and concerned citizens began calling county Extension offices daily, including the office of urban entomologist Dr. Dan Suiter. Though puzzled at first, Suiter eventually identified the insect as “kudzu bug”, an exotic insect never before seen in the U.S.

The kudzu bug, Megacopta cribraria, is native to Asia, where it is widely distributed. As its name implies, its preferred host plant is the invasive weed, kudzu. No one knows how it got here, but like many invasive pests it made itself at home quickly. Highly mobile, within a year the kudzu bug had spread to 60 north and central Georgia counties. Two years later every county in the state was infested.

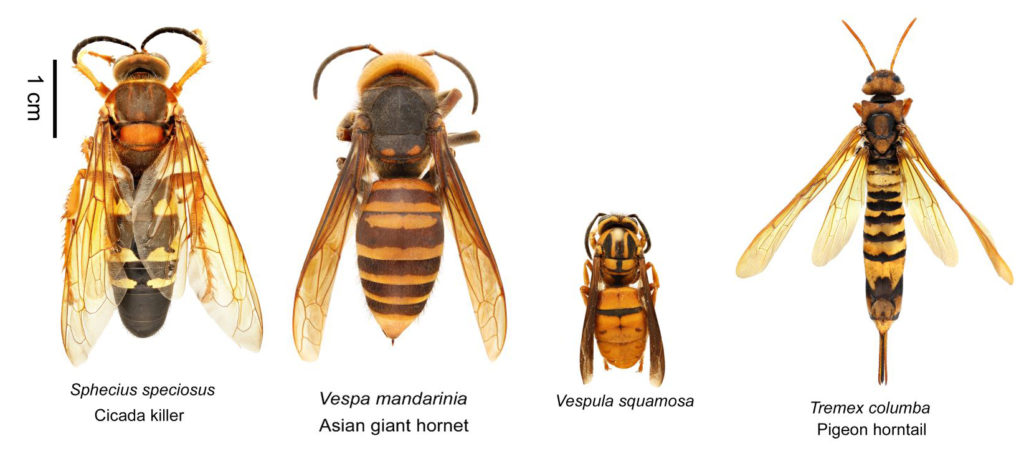

Description

It is hard to mistake kudzu bug for anything else. It is beetle-like in appearance with a unique, four-sided, ovoid shape. It is greenish-brown and shiny, up to 1/4 inch-long (3.5-6 mm). Like other true bugs in the order Hemiptera, it uses its piercing/sucking mouthparts to feed on sap. It is found mostly on kudzu but will feed and reproduce on other legumes.

Kudzu bugs feeding on the stems of soybeans in a Georgia farm field. Photo by Phillip Rogers via Bugwood.org.

The kudzu bug’s second favorite food is soybean, into which the bugs move during mid-summer. The first generation of bugs emerge during April when the bugs may cluster on non-food plants before moving to kudzu. The second generation may move from kudzu into soybeans or other legumes such as edamame, sweet peas, snap beans, cowpeas, lima beans and wisteria, where they are available.

Is it a good bug?

Kudzu is also known as the foot-a-day plant because of its fast growth.

Anyone familiar with the weed kudzu will be excused for thinking that having kudzu bug might be a good thing. After all, one of the reasons kudzu is such a horrible weed is that few things eat it. Wouldn’t it be good to have an insect to keep kudzu in its place?

That’s what the good folks in Georgia hoped. But according to Georgia extension entomologist Phillip Roberts, their optimism didn’t last. “The first years we saw what we thought was a lessening of the kudzu problem. Other weeds seemed to be competing more effectively with the kudzu.” But after a year, he said, the kudzu seemed unfazed. “We cannot see any noticeable decline in kudzu growth since the beetle moved in.”

Household pest

Kudzu bug is one of a few agricultural pests that can become an household pests. In Georgia kudzu bugs invade homes especially homes near kudzu patches. According to Suiter, unlike the multicolored Asian lady beetle, kudzu bugs are attracted to buildings but rarely come indoors. “We never really see them getting inside,” he said.

Nevertheless, if it’s your home, you will doubtless be unhappy to see thousands of bugs clustering on any white-painted parts of your house such as gutters, siding and around windows. Attempting to pick up the bugs with your hands is also not a good idea because the bugs have an odor and secrete an irritating, yellow-fluid that stains skin.

Kudzu bug activity around structures is most noticeable in the fall when the bugs begin to seek out protected overwintering sites.

The good news

The good news is that after a few rough years, kudzu bug problems in Georgia and other states seems to be declining. Also, because kudzu is less common as a weed in Texas bugs may never become a severe problem. Click here to see if kudzu has been reported from your county.

The improved kudzu bug situation in Georgia seems to be due partly to two egg parasitiods (wasps that attack the egg stage of the bugs) and to a fungus called Beauveria bassiana. Together these natural control agents have severely reduced the kudzu bug problem in Georgia and most southern states. After being overwhelmed with calls the first five year after the bug’s discovery, today Suiter says he “doesn’t see more than 20 bugs a year” brought into his office.

What to do

If kudzu bug comes calling in your garden or home there are a few things you can do:

- Don’t worry if you see clusters of bugs on non-legume garden plants. In the spring it’s not uncommon to see kudzu bugs aggregating on other plants. Within a day they are usually moved on without doing any damage.

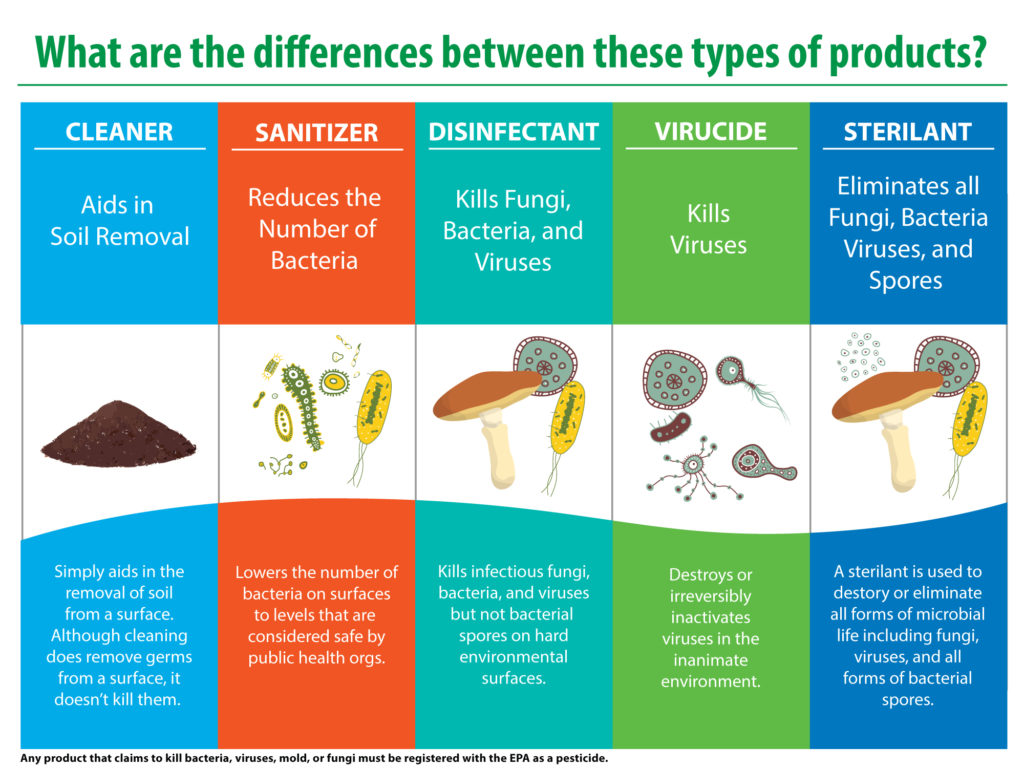

- Most insecticides labeled for garden use should kill kudzu bugs, including pyrethroid insecticides and malathion.

To kill kudzu you must remove the crown. The crown consists of meristem tissue from which new sprouts emerge. Roots lack this tissue and cannot regenerate once the crown is removed. Photo courtesy Matt Frye.

- If kudzu is present around your home, get rid of it. Though control of kudzu on a large scale has been difficult (impossible?), removing small patches of kudzu is possible with diligence.

- Crown removal. This is easiest in the spring when new growth is just emerging and before vines become inpenetrable. Look for main nodules (crowns) from which new growth is emerging and hack out using a maddox or other strong digging tool. According to Dr. Matt Frye of Cornell University in NY, pulling vines does not work, but removing the crown at this time will kill the plant. It is not necessary to dig out the entire root of kudzu (which can extend 1-15 feet deep!) to kill it. For an excellent explanation of crown removal and biology of kudzu, click here https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/69490/kudzu-six-years-NYSIPM.pdf

- Herbicides can also be used to kill kudzu, but may require re-treatment over several years to completely kill the plant.

- Around the home in the fall treat underneath eaves and any cracks or crevices where bugs are aggregating. The pyrethroid insecticides bifenthrin and lambda-cyhalothrin are reported to be among effective insecticides.

If you find what you believe are kudzu bugs we would love to get samples or see a clear photo. Save specimens to bring to your county Extension office for official confirmation, or send a digital photo. In this way you can help us track the spread of kudzu bug within the state. For more information on kudzu bug see https://www.kudzubug.org/

POSTSCRIPT: According to the USDA/APHIS, kudzu bug has previously been reported from Rusk and Upshur counties in Texas, going back as far as 2016. This is the first record, however, reported to Extension or to the entomology department at Texas A&M. This indicates the insect has been here for several years and is likely well established in multiple counties. We are still interested in reports of the insects or its damage.